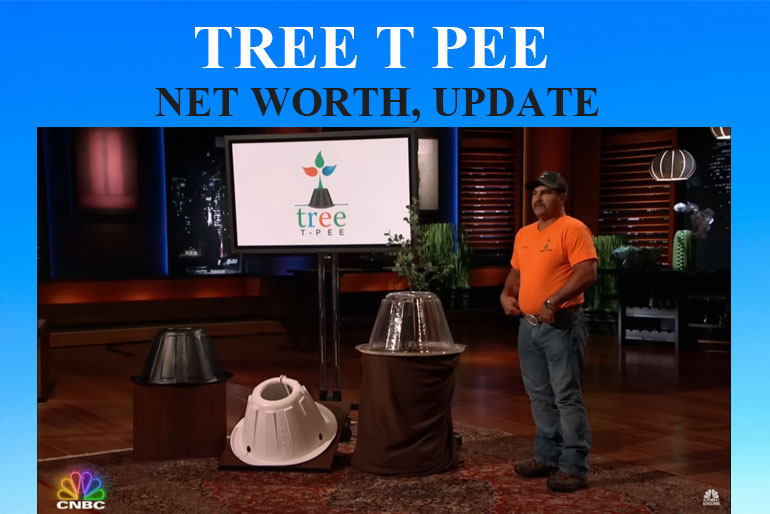

Back in November 2013, Shark Tank viewers watched a soft-spoken Florida citrus grower named Johnny Georges stroll onto the carpet holding a black plastic cone and a photo of his late father, an irrigation pioneer. That cone, the Tree T Pee, wraps around a sapling, captures every drop from a micro-sprinkler, and keeps frost at bay on cold nights. Georges explained that an unprotected tree gulps about 25,000 gallons of water a year, while his cone trims the demand down to 800 gallons, a 3,000% improvement. He asked the panel for $150,000 in exchange for 20% of GSI Supply, his tiny manufacturing company, and insisted on selling each cone for just $4.50—even though it cost $2.95 to make—because “farmers are my people.” Guest Shark John Paul DeJoria (of Paul Mitchell hair-care fame) was moved enough to accept the deal on the spot.

Overnight fame—and a flood of orders

The episode triggered the kind of response most entrepreneurs only dream about. Within twenty-four hours, Tree T Pee’s website received roughly 56,000 emails and more than 125,000 online orders, swamping the small team that had previously been molding parts in runs of a few thousand. DeJoria’s staff rushed in to stabilize the website, line up extra molding capacity across Florida and Georgia, and hammer out bulk-resin contracts so production could leap from thousands to hundreds of thousands of units in a single quarter.

How the cone actually works—minus the tech jargon

Imagine a rugged traffic cone flipped upside-down. The latest Tree T Pee is 13 inches tall, 28 inches wide at the base, and has an 8-inch opening at the top for young trunks. A micro-sprinkler or drip emitter sits just above the soil line and sprays inside the cone; water that would normally run off into bare ground now pools around the roots and soaks straight down. The shell also traps radiant heat on cold nights, nudging soil temperatures up just enough to protect tender blooms from a sudden frost. Farmers get deeper roots, lower herbicide bills, and healthier trees without installing costly fan heaters or running diesel pumps all night.

A necessary price bump and new retail doors

Shortly after the TV appearance, Georges nudged the price to $9.95 to cover thicker, UV-stabilized plastic and a sturdier locking tab. Even at that higher sticker, the cone stayed affordable compared with the cost of diesel, fertilizer, or lost crops. The extra margin let GSI Supply bring molding in-house at its Arcadia, Florida, plant, adding steady local jobs. Within a year, Home Depot listed the cone online, and independent farm-supply shops from California to Georgia began stacking pallets next to drip-irrigation parts.

Revenue milestones and a nine-digit valuation

Because GSI Supply is privately held, audited statements are scarce, yet several business sites paint a consistent picture: annual revenue hit roughly $5 million by late 2021. Apply the conservative three-times-revenue multiple used for ag-hardware deals, and you get a $15 million valuation then. Fast-forward to 2024, after global expansion and repeat orders, and most analysts place the company’s worth near $100 million.

Going global—80 countries and counting

Water stress is universal, so demand didn’t stay inside U.S. borders. Using DeJoria’s international network, Tree T Pee expanded to roughly 80 countries within a decade—olive groves in Spain, mango orchards in Australia, argan cooperatives in Morocco, and more. Overseas partners license the design, mold cones from recycled local plastic, and send royalties back to Florida, allowing GSI Supply to grow without building factories on every continent.

Design tweaks and durability upgrades

While the silhouette still echoes the original prototype, the Tree T Pee has matured. Those official 13-by-28-inch dimensions remain, but new internal ribs add stiffness, and a perforated lip lets growers zip-tie the cone to a stake in windy orchards. Old and new units slot onto the same micro-sprinkler hardware, so farmers can gradually add protection row by row.

Partnering beyond the farm

In 2024 the company teamed up with Tropica Mango Nursery in Arizona to bundle cones with specialty saplings for hobby orchards, tapping a backyard market Georges once overlooked. Around the same time, a modest merchandise line—caps, stickers, sling bags—hit the website, turning customers into walking billboards at farm shows.

Farmer-to-farmer evangelism

About five percent of gross sales now funds what Georges calls “farmer-to-farmer evangelism.” Three-cone demonstration kits ship free to county extension offices and FFA chapters, where students track moisture savings with rain gauges and present findings at local fairs—grass-roots marketing that glossy ads can’t match. Quarterly webinars on climate-smart irrigation usually draw several hundred participants, each walking away with a coupon code for a first purchase.

Social storytelling beats slick ads

Even though the brand’s Instagram feed fell quiet in 2017, engagement exploded on Facebook and TikTok. Short clips of Georges surprising small orchards with free pallets of cones routinely top 2 million views. The formula—real farmer, real data, genuine emotion—costs almost nothing and keeps the order queue healthy.

From virgin resin to a closed loop

Early production relied on virgin polyethylene, but 2016 supply hiccups nudged GSI Supply toward recycled agricultural-film scrap. By 2018 every cone was 100 percent recycled plastic, shaving roughly two pounds of CO₂ equivalent off each unit. Worn-out cones can be sent back, ground into pellets, and molded anew, closing the loop and turning a farm-waste problem into fresh inventory.

Critics, delays, and reality checks

Skeptics still voice concerns. Some agronomists argue that earthen berms or plastic mulch deliver similar savings, and Reddit threads periodically challenge the $100 million valuation. Georges counters with third-party trials showing his cone outperforming mulch on sandy soils and notes that margins stay slim by design. Pandemic-era resin shortages in 2021 did cause back-orders, but fleet-footed contract molders helped clear the backlog within six weeks.

Counting gallons, not just dollars

Internal estimates suggest Tree T Pee has saved roughly eight billion gallons of water worldwide since 2013—about the annual consumption of 90,000 U.S. households. The cone’s frost buffer has also spared growers from firing up diesel-powered wind machines, cutting both costs and emissions.

What the success means for Georges and DeJoria

Exact equity figures are private, yet insiders peg Johnny Georges’ stake near 64%, leaving 20% for DeJoria. If the firm truly sits at $100 million, Georges holds paper wealth of about $64 million, while DeJoria’s slice is worth $20 million—handsome growth on a $150,000 check. Friends say the founder still pays himself a farm-manager salary and plows surplus cash into R&D, including a biodegradable cone made from rice-husk resin and a sensor add-on that logs in-cone soil moisture.

The 2025 game plan

As of August 2025, the flagship cone still lists for $9.95, a price that hasn’t budged in almost a decade. Holding that line matters, because commodity prices swing wildly and growers budget seasons ahead. Next on the agenda: a push into European vineyards facing strict groundwater quotas, plus a Spanish-language media blitz rolling out ahead of harvest.

The takeaway

From a tear-jerking Shark Tank segment to a global water-saving brand valued in nine digits, Tree T Pee shows that simple, purpose-driven innovation can reshape an industry. The tough little cone helps farmers stay profitable, conserves billions of gallons of water, and stands as proof that technology doesn’t always need Wi-Fi or silicon to change the world. Johnny Georges may never chase Silicon Valley valuations, but he’s already delivered something many founders only imagine: lasting good for people, profit, and planet—all at once.